The field of payment technologies is evolving rapidly. Over the past decade, digital innovation has driven a diversification of payment solutions. Today, we see a wide range of technologies: payment apps for in-store and peer-to-peer transactions, mobile platforms issuing special monies (Zelizer, 2011), and money-like tokens such as airtime credits, loyalty points, gift vouchers, in-game currencies, and even customer data (O’Dwyer, 2023). These developments have introduced new actors and infrastructures, creating a digital payment economy (Elder-Vass, 2016) that fuels innovative business models, products, and services.

From Fees to Data: A Shift in Business Models

This transformation is not limited to how we pay. The entire payment ecosystem has shifted from fee-based models to marketing-driven approaches, where transaction data is monetized (Maurer and Swartz, 2017; Swartz, 2020). These changes reshape relationships and dynamics within the networks that underpin everyday payments.

A Sub-Project on the Digital Economy of Payments

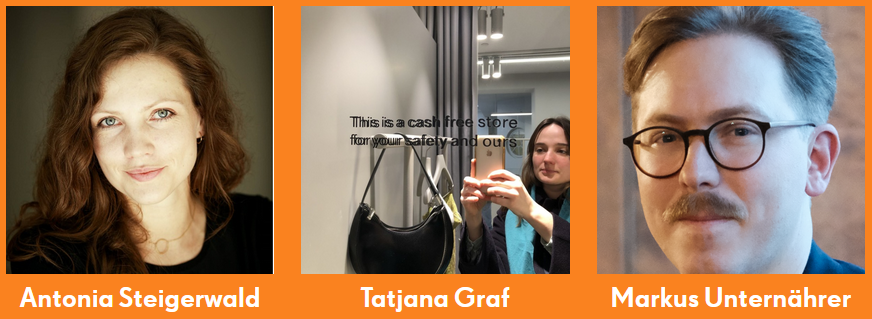

In a sub-project we examine how the practices and mechanisms of the digital economy are translated into payment technologies and embedded in socio-technical infrastructures. Insights from economic sociology, the anthropology of money, and digital marketing show how payments and transaction data are used to observe individuals, integrate them into systems, and shape relationships (Coll, 2013; Mützel, 2024; Zelizer, 2011). Studies on the data economy explain how data is monetized and infrastructures are built (Fourcade and Kluttz, 2020; Lauer, 2017; Mellet and Beauvisage, 2019). Combined with Science and Technology Studies (STS), these perspectives reveal how payment infrastructures merge social and technical elements to enable, shape, or transform relationships (Bowker and Star, 1999; Latour, 2005; Helmond, 2015; Tkacz, 2019).

This project contributes to understanding how technological innovation and shifting expertise create new relationships and markets. Proposed is an analytical framework for socio-technical change, illustrated through payment systems. It identifies three phases: anticipation, negotiation, and institutionalization. The anticipation of a data-driven future and marketing concepts guiding actors performatively shape subsequent developments.

The observation of the payment systems field concludes in 2025 and looks ahead: under the imperatives of data and extraction, payment data has become a valuable resource, monetized on virtual markets for personalized advertising.

Further Reading

- Bowker, G., Star, S. (1999). Sorting things out. Classification and its consequences. Cambridge. MIT Press.

- Callon, M. (1998). The laws of the markets. Blackwell.

- Elder-Vass, D. (2016). Profit and gift in the digital economy. Cambridge University Press.

- Fourcade, M. & Kluttz, D. N. (2020). A Maussian bargain: Accumulation by gift in the digital economy. Big Data & Society, 7 (1), 1–16.

- Kjellberg, H., Hagberg, J., & Cochoy, F. (2019). Thinking market infrastructure: Barcode scanning in the us grocery retail sector, 1967–2010. In M. Kornberger, G. C. Bowker, J. Elyachar, A. Mennicken, P. Miller, J. R. Nucho, & N. Pollock (Eds.), Thinking infrastructures (pp. 207–232). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Maurer, B. (2012). Payment: Forms and Functions of Value Transfer in Contemporary Society. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 30 (2), 15–35.

- Mellet, K. & Beauvisage, T. (2019). Cookie monsters. Anatomy of a digital market infrastructure. Consumption Markets & Culture, 23 (2), 1-20.

- Swartz, L. (2020). New Money: How Payment Became Social Media. Yale. University Press.

- Zelizer, V. A. (2011). Economic lives: How culture shapes the economy. Princeton University Press.